Friday, January 26, 2007

Behind the Wheel

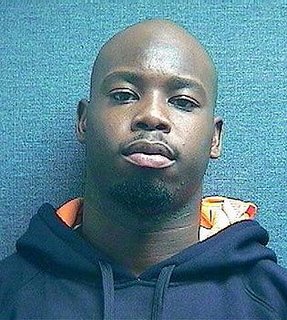

So I'm a little late on this one (I know I know, you missed me), but another Bengal got arrested and everyone went apeshit. People have been throwing their moral outrage around like Wii controllers with defective velcro. The Enquirer ran an awesome "Bengals rap sheet" sidebar in an article about the arrest that lists the series of infractions the club has racked up since the beginning of 2006. Also Marvin Lewis, dangerously close to taking some of my advice from September, invited a cop to speak to the Bengals about the dangers of driving under the influence before the season ended, and the Bengals have now created a 24 hour hot-line for their presumably hammered employees to call when they need a ride. More recently, Mike Brown even came out from his self-imposed media exile after Chris Henry's sentencing (one of his previous charges ) to talk tough (Henry served two days for being around minors while they were drinking alcohol and received a saucy tongue-lashing from the judge at the hearing to boot).

This is all great stuff really, if you're into the whole athletes are destroying the moral fiber of society thing. I'm not so much. And believe me, that's not to say it isn't very frustrating to root for a team that can't seem to get its shit together (on or off the field). But I'm ready to look at this last incident in a completely different way than the other arrests. I think we actually took a step forward here, and I'll tell why:

1. Joseph had a designated driver.

He assessed the situation and determined that the chick he was with was the number one sober. That's solid work there. Is it really his fault that she can't drive?

2. Dude was carrying his weed in a Super Bowl LX bag, next to a video game system.

You see? These guys are thinking about what it takes to win championships. I see this as kind of like that thing that Riley did with the Heat last year where he had everybody put all this important shit in a bowl or something to motivate the team. Which means that Joseph was probably on his way to pick up one of Henry's guns, Steinbach's boating license, Odell's "peanut butter crank", and AJ Nicholson's lifted stereo to stuff it all into the bag. Then Marvin was gonna put a padlock on the bag, give a motivational speech or two, and the Bengals were gonna fly through next season and win the Super Bowl by two touchdowns. Too bad the cops had to go and fuck up the whole plan.

3. Maybe I'm a glass half-full guy, but isn't this arrest #1?

People like to say that 9 Bengals have been arrested, I guess because that sounds like a big number. But really, it's 2007 people. Let's put those 8 other arrests (from 2006) behind us. And you can't keep counting Henry, okay? It's not fair. That's like calling traveling on your 6 year old cousin in a family pick up game. Just bad form. And for the record, I predict only 5 (non-Henry) arrests for the Bengals this year (a pretty significant decrease). Let me know if you want the over or the under.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

2 comments:

BURNING MEMORY: '89 Super Bowl

By Hal Habib

Palm Beach Post Staff Writer

Monday, January 29, 2007

This was the stolen Super Bowl.

Stolen from the city of Miami, which spent as much time fretting that week in 1989 as it did celebrating, because it's difficult to throw a party when a mob is throwing rocks and bottles and burning cars.

Stolen from Stanley Wilson. Or by him. Wilson, a Cincinnati Bengals running back, never got a chance to beat the San Francisco 49ers that Sunday evening because he couldn't beat his cocaine addiction on Saturday evening, forever making Room 2211 at the Plantation Holiday Inn a notorious piece of Super Bowl trivia. Even in his haze, Wilson might have sensed the magnitude of his mistake, crying to coach Sam Wyche, "Sam, I'm so sorry, I'm sorry." By then, Wyche knew Wilson's career was finished.

Stolen from all of us, because as dramatic as the game was, coming down to a Joe Montana touchdown pass to John Taylor with 34 seconds left, no one will ever know if Wilson could have made a difference on a sloppy field suited to his style.

It is six days until South Florida hosts its ninth Super Bowl. It's a good bet the week will bear little resemblance to the time Miami welcomed its sixth title game.

"Man, is this really what happens here? Is this the way Miami is?" Those were the questions Bengals receiver Eddie Brown fielded that week from teammates. Brown, from Miami, and fellow receiver Cris Collinsworth, from Titusville, had talked excitedly after winning the AFC championship about not only going to a Super Bowl, but going to one "back home, a blessing for any athlete," as Brown says.

And then? Then they would gather, in disbelief, on the balconies of their first hotel, the Omni in downtown Miami. The trouble was nearby.

"A long field goal away," as Bengals kicker Jim Breech described it, rioting had broken out after William Lozano, a white off-duty police officer, fatally shot a fleeing black motorcyclist, Clement Lloyd, on Martin Luther King Day, the Monday before Super Bowl XXIII.

Within hours, more than 1,000 officers had been called in but couldn't regain control in predominantly black Overtown. By Tuesday night, eight people were confirmed shot, one fatally, and more than 230 arrests had been made.

"We were watching the movie Mississippi Burning, and when I came out, everyone was scurrying about," says Solomon Wilcots, a Bengals cornerback who will work as a CBS sideline reporter Sunday. "I thought it was eerie. I said, 'Man, I just came out of Mississippi Burning and came to see Miami burning.''"

Says Wyche: "From one side of the hotel you could see the fires that were being set at night."

The 49ers, staying near Miami International Airport, didn't encounter trouble, and for the most part the Bengals were escorted or directed away from it. Their cocoon burst 22 hours before kickoff when Wyche broke down in front of the team. At first, quarterback Boomer Esiason wondered if Wyche was up to his old motivational tricks. Then the reality of what Wilson had done sunk in.

"It reverberated beyond shock, to see your head coach crying when your expectation is this is going to be the inspirational moment that every coach covets," says former Bengals linebacker Reggie Williams, current vice president of Disney Sports in Lake Buena Vista. "It hurt everyone. There was a certain belief and trust you had, not only in Stanley. That's the glue that holds a team together and that glue had disintegrated before our very eyes. And there was nothing we could do about it. We're haunted the rest of our lives and always wondering, 'Would we have won had Stanley played?''"

Despite the 20-16 defeat amid tragic circumstances, Esiason still considers that Super Bowl a "very positive memory, a great memory. It's something I'll hold with me for the rest of my life."

Says Wyche: "It's something that everyone wants so desperately to be a part of and only a handful of the players ever get a chance to do it. So, yes, it's one of the best experiences I've ever had."

Imagine if a piece of it hadn't been stolen.

A surreal scene

In a time of Crockett and Tubbs, one motorist on Interstate 95 saw what looked like a riot and thought, "Maybe they're filming Miami Vice." Then a bottle flew through his window. Incidents like that received national attention from sports reporters who thought they'd be writing about football.

Among the tales: Wilson was driving to dinner Tuesday, heading for I-95. At the top of the entrance ramp, he encountered a group of youths who began pelting his rental car with rocks and bottles.

"I was very intimidated, and I'm not a guy who is easily intimidated," Wilson said at the time. "It was very scary. I think I'll wear my uniform next time I go driving."

There was more chaos than anyone could absorb in Miami's fourth disturbance since 1980. Speculation surfaced that the Super Bowl might move to Tampa.

Dick Anderson, the former Dolphins safety and chairman of the host committee, today says "it may have been talked about," but optimism reigned. One thing is certain: "I actually broke out in tears on Tuesday night," he says, although every Super Bowl-related event went off as planned.

Not so for the Miami Heat. Its game against the Phoenix Suns, scheduled for Tuesday night, was postponed indefinitely after a crowd of about 100 advanced on Miami Arena, breaking car windows.

"I remember being in the building at 6 o'clock for a 7:30 game," then-coach Ron Rothstein says, "and a half-hour later (managing partners) Billy Cunningham and Lewis Schaffel were going around - there were maybe 100 people in the building - and shooing everybody out.

"The city of Miami, without telling the NBA, telling anybody, called the game off. ... There was burning and rioting going on two blocks from the arena and it was like every man for himself."

Looters carried sofas from stores, the police powerless to stop them, while entrepreneurs seized their opportunity by hawking T-shirts that read, "Miami Super Bowl '89. It's a Riot!"

Some players saw things in another light. Wilcots implored people to stop talking about what was happening and start discussing why. Williams, a councilman in Cincinnati at the time who had lived in Miami during one off-season, visited a juvenile-offender program in Overtown during the unrest. Williams says he answered pointed questions by telling youngsters "their hope lay in their opportunity, not in their incarceration."

No doubt the Bengals thought their troubles were behind them when they moved to Broward County the night before the game.

How wrong they were.

Bengals hit another obstacle

"Why would you do it? A lot of people were counting on you."

That's what Eddie Brown says he would tell Stanley Wilson if he were talking to him today. But Brown hasn't talked to his roommate since that night. Only a few Bengals have.

Today, Wilson, 45, is in a California state prison, eight years into a 22-year sentence. He was caught stealing $130,000 in property from a Beverly Hills home to pay for drugs. In 1999, Collinsworth visited him, as much to get answers for himself as to interview Wilson for Fox Sports.

"My God, what have I done?" Wilson told Collinsworth.

Wilcots, too, interviewed Wilson, for ESPN. Having grown up in a neighboring California community, Wilcots long knew of Wilson and his family. "A very charming guy," Wilcots says.

Stanley Wilson, the inmate? "He was hurt," Wilcots says. "He was hurt with all the pain he had caused so many people and things he had done. He felt bad he had wasted so much time and so much potential. I was kind of there just to love him, to offer him encouragement. I'm asking questions but still trying to let him know I'm there to support him."

It's unlikely that feeling was always mutual among the Bengals. Months after the incident, Wilson's agent, Reggie Turner, told The New York Times that five Bengals were "involved" in drug use. In 1990, Wilson sold his story to Penthouse magazine, naming Brown, among others.

Brown says it was "fabricated just so he could get paid."

"They added guys into something and that's not right, just to clear his name, to really make him look good," says Brown, current receivers coach for the Arena League's Las Vegas Gladiators.

"So untrue," Wilcots says of the allegations. "I know for a fact because Stanley's room was right across from mine. I remember we all got on the elevator together and when the door was closing, he jumped off and said he had forgotten his playbook and he went back by himself to get his playbook. All of us were going down the elevator to the team meeting and Sam says, 'Is everyone here?''"

No.

In the bathroom of Room 2211, Wilson was snorting and smoking cocaine.

Running backs coach Jim Anderson, who had virtually adopted Wilson to keep him out of trouble, was among those who went to his room.

"I saw something I didn't want to see," says Anderson, still reluctant to go into detail about what happened next. "I think he was very embarrassed."

Anderson wasn't the only one with a personal stake in Wilson.

After every home game, Wyche recalls, "we had a little deal where he would come over to my house and have ice cream. The reason for that was to calm him down a little bit because the psychiatrist had told us that you're most vulnerable to get back into drugs when you're extremely high or extremely low, when you're celebrating or you're depressed. Of course, after a game, you're one or the other."

The night before the Super Bowl, Anderson, a hotel executive and the team's security chief, went to Wilson's room and opened the bathroom door with a coat hanger. They found Wilson hiding behind a shower curtain, sweating.

"I can still remember him crying on the side of the bed and saying, 'Sam, I'm so sorry, I'm sorry,''" Wyche says. "And, of course, it was too late."

Wyche, also in tears, returned to the meeting room and announced, "Stanley couldn't make it." He told players to reconvene 10 minutes later because he was unable to go on.

Wilson was quickly moved back to the Omni but disappeared via a back stairwell or fire escape. Then he checked into a rundown hotel, sending a street dealer to purchase more cocaine.

He never saw the Super Bowl, not even on television.

Who knows what might have happened had Wilson been on the field? Wilson gained only 398 yards with two touchdowns in the regular season, but he scored twice in a playoff victory against Seattle, was key to Cincinnati's play-action offense and was the primary blocker for James Brooks and Ickey Woods.

Williams says he spent Saturday night reassuring Brooks, his roommate.

"You can have a great game, the greatest of all time, you're going to run so fast they can't touch you," Williams would say.

"Tell me again, Reggie, tell me again," Brooks would reply.

"A very emotionally draining night," Williams says.

So was the next night. Wyche, remembering the treacherous footing at Joe Robbie Stadium, says Wilson might have been particularly effective. "He didn't pick his feet up and really dig into the turf," Wyche says. "I think he could have made people miss."

A 40-yard field goal by Breech with 3:20 left gave the Bengals a 16-13 lead, but on the other sideline stood Montana, Joe Cool, who took time in the huddle to point out actor John Candy in the stands. Unfortunately for the Bengals, Montana turned serious quickly enough. Eleven plays and 92 yards later, it was 49ers 20, Bengals 16.

"Instead of going to Disney World," Esiason says, "I went to Aruba."

Dealing with the aftermath

The weekend had ended. The effects lived on.

Wilcots couldn't sleep for a month.

"My life changed that day," Williams says. After 14 seasons with the Bengals, he retired.

"When I was drafted by Cincinnati, my one and only goal was to win a Super Bowl ring," he says. "If I didn't win, it was time to leave town. ... I never wanted to live the rest of my life making excuses for 34 seconds, so I left Cincinnati while on top. But 34 seconds short of a ring."

And Stanley Wilson? Stanley Wilson might someday appear in a Super Bowl, oddly enough. Stanley Wilson Jr., a cornerback, was a third-round draft pick by Detroit two years ago. This season, he was named the Lions' most improved player.

In 2005, Wilson Jr. told The San Jose Mercury News that he never discussed the 1989 Super Bowl with his father and didn't consider his name a burden.

"There is nothing I would like more than to make it to the Super Bowl and to win it," Wilson Jr. said.

Winning a Super Bowl is special, but as the Cincinnati Bengals learned, qualifying for it - and playing in it - can be special, too.

"The Super Bowl is something you have to cherish," Brown says. "I do cherish that, for the rest of my life. Even though that happened, we still have to look past that, knowing we were in the best game ever played."

And one of the strangest.

So does that mean you're taking the over?

Post a Comment